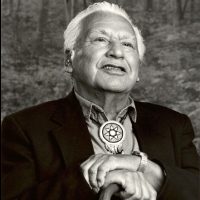

Robert Bushyhead

Cherokee tribal elder Robert Henry Bushyhead called his native Kituhwa dialect a gift of the Great Spirit. With the help of his daughter Jean Blanton, a teacher in the Cherokee schools, he devoted years to documenting this legacy. The preservation process began years before that, however, when he not only developed a love of his native language but also a gift for telling the stories of what it means to him and to the Cherokee people.

Born in 1914, he grew up in the Birdtown community of the Qualla Boundary, living with his mother, father, and older brother in a one-room log cabin. Kituwha was the only language used by his families and friends. It bound them to each other and to nature as well. But his boarding-school teachers insisted that he abandon the Kituhwa dialect and speak only English. “When I was seven years old, my father enrolled me in the government boarding school in Cherokee. One of the first things they taught us, I guess, was discipline. And in that line of discipline there was a thing that they wouldn’t let us do, and that was to speak the Cherokee language. And many times we went down into the furnace room where nobody would see us and start talking Cherokee. We would just be getting started good when they caught us. And they punished us as violently for speaking the Cherokee language as they would have if they caught us smoking or chewing. And the thing about this was that those who became parents did not teach their children the Cherokee language lest they go through the same punishment.”

When he had the opportunity to complete his education, he mastered English, became a Southern Baptist home missionary to the Eastern Cherokees and then a traveling evangelist. He also took an interest in performing in the outdoor drama about the Cherokee, Unto These Hills, in which he brought great distinction to the role of Elias C. Boudinot.

Robert Bushyhead worked with his daughter and a local videographer to record the sounds of his native language along with its grammar. “No other language sounds exactly like it, and we want to preserve this,” he said. “We have all of those sounds—there are eighty-five of them—and just a little inflection makes all the difference in the world. Cherokee has a flow, it has a rhythm that is beautiful. And once you lose that rhythm, then, of course, you’re lost.”