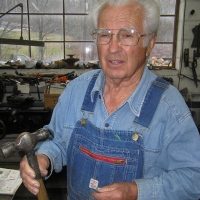

Bea Hensley

Bea Hensley

Bea Hensley learned blacksmithing from Daniel Boone VI, who came from a long line of blacksmiths. Bea pounded metal all of his life, and he helped keep the tradition alive by teaching his son, Mike. “I’ve been at it sixty-five years,” said Bea. When Bea was four years old, his family moved from Tennessee to Burnsville, North Carolina, and they settled right beside Daniel Boone VI’s smithy. Bea was fascinated with Boone. “I used to stand in the door and watch Daniel in his shop, he said. “He used to make the prettiest little buggy and wagon that you ever laid your eyes on. It had the tongue in it and everything just like a big wagon.” Bea started his metalworking by flattening copper wire to make intricate hands for pocket watches. After high school, Bea inquired about working for Boone to apprentice with the master. Boone recognized Bea’s talent and took him into the workshop.

“When I was about 15, everybody had a horse to shoe. Some people had a number of horses to shoe,” he explained, talking about his early blacksmithing days. In addition to shoeing horses, he worked on pieces used for carriages or logging such as ‘J’ bars and grab skips. In 1937, when Daniel Boone VI received the exclusive contract for restoration ironwork to be done in colonial Williamsburg, he built a new forge in Spruce Pine as his base of operations. After World War II, Bea Hensley returned to the forge to help with the restoration work, and it was he who finished the job in the early 1950s.

After buying the shop from Daniel Boone VI, he went into ornamental ironwork full time. Over the years, he mastered forms from candlesticks and candelabras to giant ornamented metal gates and exquisite knives. He made pieces for rich and famous and has customers all over the world. Bea worked as a foreman for the Gunner Machine Company for about ten years, but he returned to his first love, blacksmithing.

Bea taught his son Mike the language of the anvil, which he learned from Daniel Boone VI. According to tradition, this method of communicating instructions between blacksmiths dates back to biblical times. Bea received a North Carolina Folk Heritage Award in 1993 and the National Heritage Fellowship Award from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1995.

Bea Hensley passed away on April 11, 2013 at the age of ninety-three.